What is Kabbalah?

I refer to it from time to time in my essays. The ideas appear quietly, usually as metaphor or conceptual framing in support of ideas I seek to convey. Until now, I’ve not really expounded upon the tradition.

Perhaps I should.

In contemporary culture, Kabbalah has become familiar without being understood. It circulates not through texts or study, but through celebrity endorsements, lifestyle branding, and the promise of personal transformation. What is presented under that name often bears little resemblance to the tradition itself. Before continuing further, it is necessary to pause and orient—to say plainly what Kabbalah is, what it is not, and why it matters.

This is not so much an essay that teaches Kabbalah as an essay that seeks to clarify and put it back in its proper place.

The Problem with “Mysticism”

The word mysticism has been terribly misconstrued over the years, especially in this post-modern culture obsessed with esoteric knowledge.

In common usage, it has come to suggest the irrational, the magical, or the vaguely supernatural. Mysticism is imagined as intuition untethered from discipline, experience without structure, or insight divorced from responsibility. None of this accurately describes mysticism as it has been traditionally understood, nor does it describe Kabbalah.

Properly understood, mysticism arises not from the rejection of reason but from its very limitation. It appears where language proves inadequate to the subject at hand. Modern science has logic, reason, and the scientific method to build its concepts within sensible constraints. Religion seeks to make approachable that which lies beyond the boundaries of science. Mystical traditions do something similar when speaking about G-d, creation, and ethics.

Kabbalah is mystical not because it is vague, but because it places constraint around that which cannot be expressed otherwise, all while allowing room for the expansion of ideas.

Kabbalah as Philosophical Theology

At its core, Kabbalah is a philosophical system much like any other. It is concerned with a very old problem: how an infinite G-d relates to a finite world.

Classical theology can speak of divine attributes—justice, mercy, unity—but it struggles to explain process. Scripture describes encounter and consequence, yet leaves many questions unresolved. These describe well the what, but not so much the how.

Kabbalah emerges as a language for the higher questions of the how.

It assumes that G-d is, by nature, unknowable. Speculation beyond what is seen and experienced is both impossible and inappropriate. Instead, it speaks about relationship—about how divine presence is experienced, mediated, constrained, and revealed within creation. It is not speculative, not superstition—it is observational. More importantly, it does not replace Torah; it presumes it…deeply. Detached from covenant and obligation, Kabbalah ceases to make sense.

Symbolic Language

Because Kabbalah deals with the extension of reality that is beyond direct representation, it relies on symbolic language. This is neither decoration nor poetry for its own sake; symbol functions here as a form of disciplined exchange.

A symbol does not claim to be the thing itself. It points, gestures, and aids interpretation. In this way, symbolism prevents naïve literalism and superfluous abstraction. It allows complex ideas to be held without being flattened, costing them their meaning.

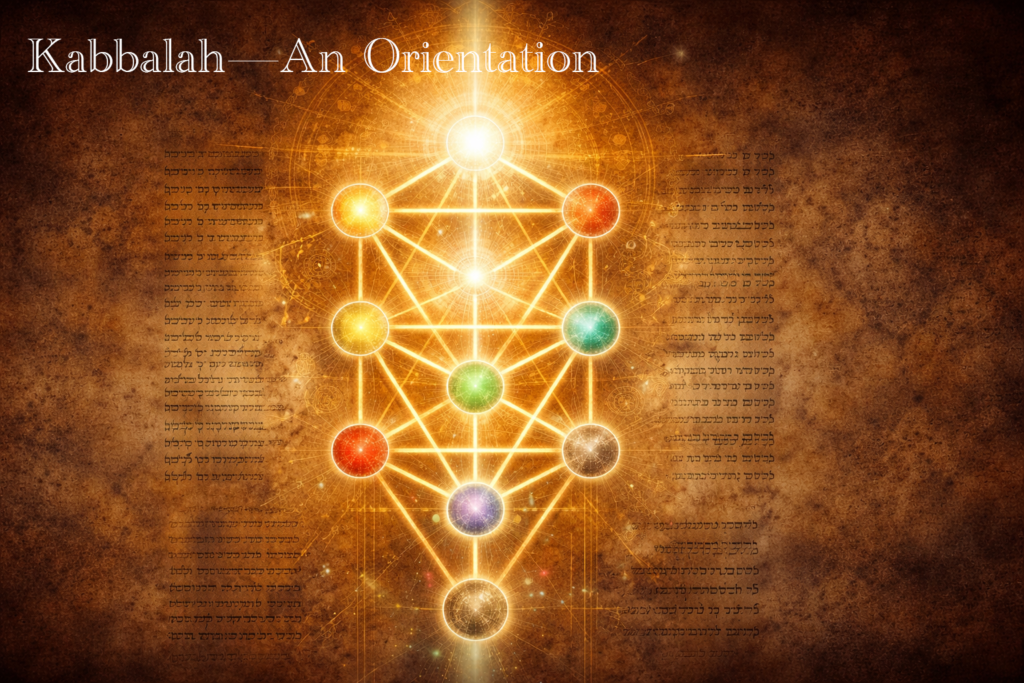

One of the most familiar symbolic frameworks associated with Kabbalah is the Tree of Life. Often misunderstood, this is not a chart of G-d, a hierarchy of spiritual power, or a cosmological map. It is a way of speaking about the flow of divinity, its attributes, and relationship—about how unity becomes multiplicity without ceasing to be one.

Within this symbolic language, the sefirotic framework—that is, the language of divine emanations—speaks of flow rather than form, describing how shefa, the outpouring of divine vitality, is mediated through creation and encountered in human life, rather than mapping G-d or enumerating powers.

Early Roots

Kabbalah did not appear out of nowhere. Its earliest concepts were already present in Tanakh and early rabbinic literature. Early texts such as Merkavah focused on prophetic visions (notably Ezekiel) and the problem of approaching divine holiness without annihilation. These were speculative, symbolic, and tightly controlled traditions held to a very select group. The concern was always the same: how does the finite encounter the infinite without breaking?

What we recognize as Kabbalah proper takes shape in medieval Europe, particularly in southern France and Spain. It was during this time that earlier ideas were synthesized into a coherent symbolic theology. The central text of this era is the Zohar, traditionally attributed to Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai but historically compiled in the late thirteenth century. It reads like symbolic commentary layered on Torah, a narrative of the collective experiences and conversations of a group of rabbis led by their peer mentor.

At this stage, Kabbalah was integrated with Torah study and predominantly concerned with divine flow, repair (Tikkun Olam), and human responsibility. There was no particular interest in mass accessibility.

Later, toward the end of the fifteenth century, Isaac Luria introduced new concepts that came to dominate later thought:

- Tzimtzum (divine contraction)

- Shevirat ha-Kelim (shattering of vessels)

- Tikkun (repair)

These ideas reframed suffering, exile, and human action within a cosmic narrative of responsibility. This greatly intensified ethical seriousness; every action mattered.

Restraint and Distortion

Gradually, Kabbalah came to be misunderstood—sometimes disastrously so. This engendered a movement of restraint. Study was restricted to those of a certain age and scholastic level. The lesson was clear: unmoored mysticism destabilizes communities when symbolic language is mistaken for literal.

Much of what passes for Kabbalah today begins by severing it from its foundations. Symbols are extracted from their ethical context, and the language of repair becomes the language of personal gain. Discipline gives way to technique; responsibility to outcome. What was once a tradition meant to discipline the ego is transformed into a means of enhancing it—recast as self-help, mysticism-for-hire, or celebrity spirituality. In the process, symbols are stripped of obligation and context, leaving behind a hollowed-out aesthetic without substance.

Serious Practice

Serious practice of Kabbalah gradually faded from mainstream Judaism. Recently, some scholars have begun the process of reawakening the historical traditions of Kabbalah, studying it not as a means of new-age divination but as originally intended: a disciplined language for understanding responsibility, repair, and the relationship between divine presence and human action.

This recovery does not seek novelty. It seeks fidelity.

Properly understood, Kabbalah is less concerned with explaining the esoteric than with observing what IS, and learning how to engage it ethically without distortion.

Discover more from Many Lamps, One Flame

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.