I find myself a bit moved today to discuss the current parashah, Shemot.

Judaism has a regular practice of Torah study. Truly, it is study of Torah that defines Judaism. The Torah is divided into 54 parshiyot (weekly portions), and one is read each week, typically on Shabbat. (Interestingly, in leap years portions are read individually, but in shorter years some are paired to keep the calendar aligned.) The weekly portion is read from a handwritten Torah scroll, using a cantillation system dating back generations. Once read, there is typically discussion and study following.

This week, the cycle moves into the book of Exodus. Exodus opens with the old generations of the Hebrews gone and the people of the book largely settled and assimilated into the land of Egypt. However, there arose a Pharaoh who did not know of the people’s former patriarch, Yosef, who had done many great things for the people of Egypt. Instead, he saw the growing Hebrew population as a problem for the nation—a people who could easily rise up and overthrow him (Exodus 1:8–10).

And so begins the tyranny of the despot.

Now, most are familiar with the book of Exodus. It has made its way into the hands of many a Hollywood director (who hasn’t seen Cecil B. DeMille’s epic The Ten Commandments with Charlton Heston, who will forever be the very vision of Moses?). However, as ancient stories are wont to do, there is a lesser character in this story—a woman—who passes with little notice. Torah is well known for its sparing emphasis on the acts of women. Only the most exceptional of women are discussed, named, or lauded in its holy script. So when one comes to the forefront (as in the opening story of Exodus), it is something that should draw attention and scrutiny.

At the time of Moses’ birth, Pharaoh had decreed that the newborn sons of the Hebrews be cast into the Nile (Exodus 1:22). This was an attempt to reduce the population and achieve greater control over his workforce. Moses’ mother, Jochebed, a daughter of Levi, gave birth during this dark time and knew her baby was in danger. She hid him for three months, and when this was no longer an option, in desperation she placed him in a basket and set him afloat on the river Nile (Exodus 2:2–3). (Side note: this basket is actually called a tevah, the same word used for Noah’s Ark; Genesis 6:14; Exodus 2:3.) Moses’ sister, Miriam, stands at a distance as witness (Exodus 2:4).

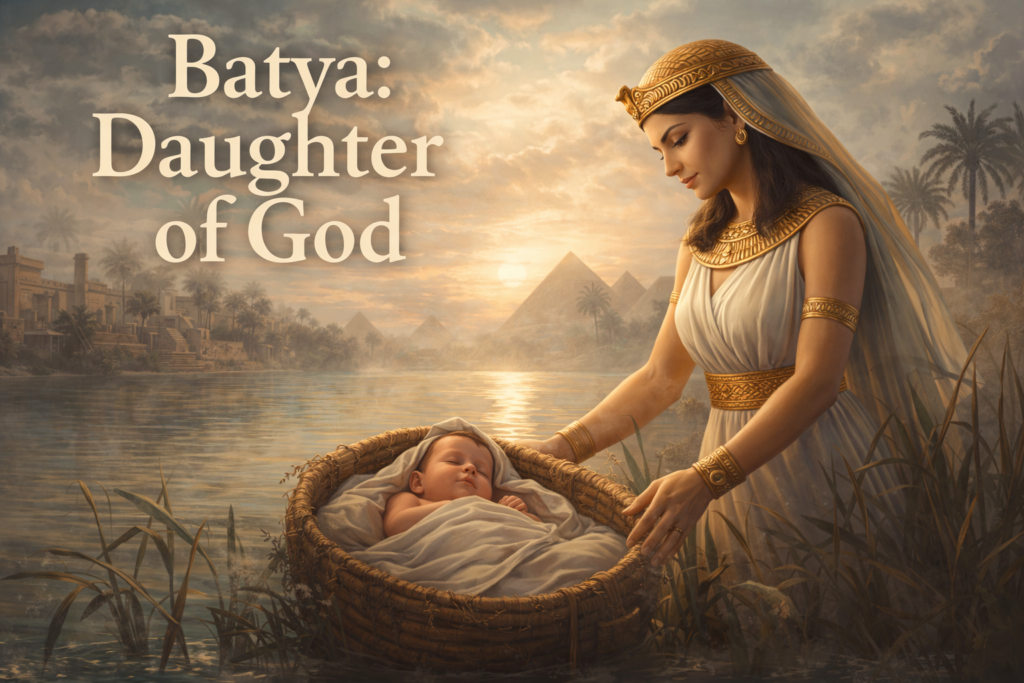

Pharaoh’s daughter—later named Batya by rabbinic tradition—comes to the river to bathe and notices the basket among the reeds, retrieves it, and has compassion upon the child (Exodus 2:5–6). She decides to keep him as her own, but of course she needs a nurse maiden. At this point, Miriam comes forth and suggests Jochebed act as wet nurse (Exodus 2:7–9). Pharaoh’s daughter names the child “Moses,” saying, “For I drew him out of the water” (Exodus 2:10), and raises him in Pharaoh’s house—educated, protected, and groomed by the very system he will one day rebel against.

One of the particularly interesting aspects of this part of the story rests with Batya, daughter of Pharaoh. Rabbinic tradition teaches that she was rebellious, disagreeing with her father’s proclamation both morally and spiritually (Shemot Rabbah 1:23; Midrash Tanchuma, Shemot 8). She knew full well this was a Hebrew child and yet defied her father’s edict.

The words used to describe her reason for going to the river further carry deeper meaning. The Hebrew verb lirḥotz does mean to wash or bathe (Exodus 2:5), but it is the same verb used elsewhere in Torah for ritual washing—by priests before service and in moments of preparatory cleansing before sacred encounters (Exodus 30:18–21; Leviticus 15; Ruth 3:3). The Nile itself is “living water” (mayim ḥayyim), later required for ritual purification. Thus, an interpretation of the text implies that Batya was not merely washing the dust of Egypt from her skin, but symbolically separating herself from the moral corruption of her father’s dynasty (Shemot Rabbah 1:23).

In this light, she acts in utter defiance of the cruel and violent decrees of the state, has compassion, and places life above all other things.

Further, this moment marks the first stirrings of redemption. Many assume redemption begins with the first plague, the turning of the Nile to blood, or perhaps at Sinai. Yet it truly begins earlier—with a woman, a river, and the audacity to choose life over fear and violence.

The very name Batya is worth noticing as well. It means “Daughter of G-d” and was given to her not by Torah (nor by her father) but by rabbinic tradition as a name bestowed upon her by heaven (Leviticus Rabbah 1:3; Shemot Rabbah 1:23). This manner of naming is not without precedent in Torah. Names are often not merely inherited but earned, bestowed at moments of moral, spiritual, or covenantal transformation: Avram becomes Avraham, Sarai becomes Sarah, and Yaakov becomes Yisrael—not as cosmetic changes, but as recognitions of who they have become through action, struggle, or calling. In this same tradition, Batya’s name reflects not lineage but moral alignment. In Torah itself, she is unnamed—simply “Pharaoh’s daughter.” She is not born into the covenant but rather enters it by moral action, a rare conferring of covenantal identity. Rabbinic literature further treats Batya as one of the righteous among the nations (ḥasidei umot ha-olam), proof that moral clarity is not ethnically exclusive and that redemption can begin outside the covenant and move inward (Shemot Rabbah 1:23). Midrash further teaches that she left Egypt with the Israelites and appears later in Chronicles as “Bitya, daughter of Pharaoh” (1 Chronicles 4:18). G-d is even said to have claimed her by name: “You called Moses your son; I will call you My daughter” (Leviticus Rabbah 1:3).

Midrash also offers a striking interpretation of the Hebrew text itself. Exodus tells us that she sent her maidservant to retrieve the basket from the reeds (Exodus 2:5). However, the Talmud reads the verse differently, focusing on the word amatah (Talmud Sotah 12b). While commonly translated as “her maidservant,” the word can also mean “her arm.” On this reading, Batya stretched out her own arm, and it was miraculously lengthened to reach the basket—far beyond a natural distance (Sotah 12b; Shemot Rabbah 1:23).

This interpretation places Batya fully at the center of the act. She herself reaches, extending beyond what was possible, embodying the principle that human initiative precedes divine assistance. Batya did not ask permission, nor did she wait for certainty—she reached. Her actions, the risks she took in saving a crying baby, and the quiet beginning of redemption are the things by which she is forever remembered.

In this, Batya embodies a principle that runs quietly but insistently throughout Torah: divine assistance does not replace human action; it meets it. G-d does not act instead of Batya—He acts through her. She reaches first, and only then does the impossible become possible. This is not a theology of passivity or waiting, but of responsibility and response. Revelation, redemption, and covenant do not simply descend upon those who stand still; they emerge where human courage creates space for them. Batya does not know the future, does not see Sinai, does not anticipate plagues or liberation. She simply chooses life, stretches herself beyond what seems possible, and trusts that the act itself matters. In Torah, that is often enough. G-d completes what human hands begin.

Discover more from Many Lamps, One Flame

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This was so well written and easy to understand. The idea that Batya leaves Egypt with the Jews is not

what we believed. Does it mean Pharaoh’s son is spared, or does

Mishnah interpret the story of Batya

differently…. or am I getting ahead of myself